Written by Toni Bruce and Esther Fitzpatrick

Factionalisation is a creative method of writing research. To make sense of data generated we employ Richardson’s (1994) writing as a method of inquiry to extend sociological understanding. Narrative forms of research, such as autoethnography, require attention to the craft of writing and have a tradition of using fictive strategies, where they ‘make use of convention such as dialogue and monologue to create character, calling up emotional states, sights, smells, noises and using dramatic reconstruction (Denshire, 2014, p. 836). The writing should provide verisimilitude, inviting the reader to believe in the plausibility of the story, and to see themselves and others as ‘human subjects constructed in a tangle of cultural social and historical situations and relations in contact zones’ (Brodkey, 1996, cited in Denshire, 2014, p. 833). However, factionalisation goes further than autoethnography through its embrace of freedom to “invent and play” (Markula & Denison, 2005, p. 113), and “to exaggerate, swagger, entertain, make a point without tedious documentation, relive the experience and say what might be unsayable in other circumstances” (Richardson, 1994, p. 521). This form of writing – which goes by other names including ethnographic fiction and collective stories – emphasizes the quality of the narrative, seeking verisimilitude, creating social worlds “where reality is not what it is, but what we make it into” (Markula and Denison, 2005, p. 113). In the rest of this blog post, we attempt to embody a key tenet of writing as a method of inquiry: that is to ‘show’ rather than ‘tell’ you what factionalisation can look like. We present two examples of our own factionalisations, first explaining the background research that underpinned our creative writing methods, and then leaving you, the reader, to judge for yourself whether our attempts have achieved our aims of creating believable characters entangled in and grappling with their cultural, social and historical contexts.

ESTHER: In the example below (Fitzpatrick & Bell, 2016), I draw on the data generated through my critical family history research and create a factionalised (Bruce, 2014) script. The purpose of the script is to give the different characters in the story an opportunity to speak to the complex and entangled nature of their relationships. Bruce (2014) argues that:

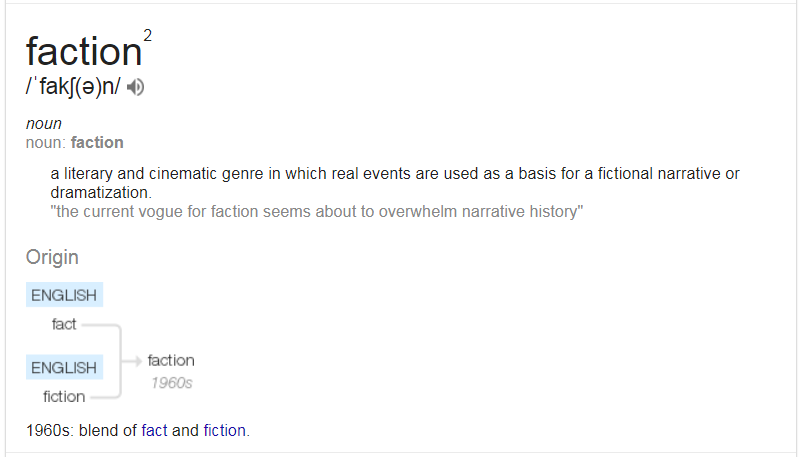

[f]actionalisation is a blend of fact and fiction, of observation and imagination. It is a form of representation that must be methodologically rigorous, theoretically informed, ethically reflexive and interesting to read, see or hear. Its aim is to dissolve the arguably artificial line between fact and fiction, and create the conditions for deep emotional understanding. (p. 6)

The act of creatively writing a script “transformed and stretched” my memory, enabling a “balance between the need to respond to the reality” of fragmentary data and the need to create a coherent story (Smorti, 2011, p. 306). Academic fiction is understood as a transformative tool that has the potential to encourage critical thinking, raise consciousness and create connection between the individual story and wider sociological understandings (Leavy, 2016). The following scripted conversations around are works of fiction, where the content of the conversations are based on historical facts. In this work imagination was applied to the gaps, drawing on plausible scenarios through considering the wider political, social and environmental factors known of the time. There is not the story, it is my story.

Data is generated through exploration of a range of historical artefacts. For the fragment of story below, Avril Bell and I had gathered acorns from the trees on our Auckland city campus planted at least 150 years ago from acorns Avril’s ancestor, George Graham, brought to New Zealand. We walked through the arch in the wall Graham had designed for the barracks. We walked by Government House where Governor Grey resided, which we knew from the archives had sat opposite my ancestor Hartog’s home. From letters we read about Hartog tutoring Grey in Hebrew and being a familiar visitor in the home. From census records, photos and other historical stories we knew the ages, whereabouts, friendships and occupations of the various characters in our stories. From Governor Grey’s letters we learn that Grey was an important friend to Kate, someone she confided in, and that she shared his love of books. I imagined a moment in our shared histories. I imagined colonial Auckland, I imagined a large wooden house opposite Government House. I then drew on the facts to create this fictive scene.

It is early evening and two men in uniform are approaching the door of a large wooden house. I see an old man sitting inside his living room. The uniformed men knock on the door and one enters.

Hartog: Welcome my dear student and friend – so Governor, have you come for another lesson?

Grey: Shalom my friend … not today … I come to…

There is a shuffle in the corner of the room and Grey turns

.. ah and here is my favourite Jewish princess. And how are you Kate?

A small girl clambers out of a reader’s daze, walks toward Grey and curtsies.

Kate: Shalom Governor Grey.

At the door a young gangly man stands waiting.

Hartog: Who’s your friend Grey?

Grey: George Graham’s boy. May I introduce you to William Australia – recently arrived back to Auckland from his studies in England. He’s helping us out with the troubles in the Waikato – speaks fluent Māori and has his father’s desire for peaceful negotiations.

Hartog beckons the young man inside.

Hartog: Shalom William Graham, welcome, haere mai, barukh ha-ba. Kate, go and get the kettle on.

Kate leaves the room.

Grey: I came to see if I could help. I see you’ve taken Kate under your wing. How are Esther and the girls getting on since Abraham’s passing?

Hartog: Kate comes over and keeps me company. She was very close to her father, a serious girl – always tucked away with her nose in a book.

Grey: She must come and visit my library; I need more friends to share my books with.

Hartog: Turns to William. And how is your father William? One day this city will thank him for his foresight when planning the barracks, imagine – a beautiful park in the middle of a chaotic city …a man of vision.

William: He is well, thank you.

He coughs nervously.

But I would like to talk to you about the goat!

Kate has entered into the room. She starts to giggle. The three men turn to look at her.

Kate: But he was so funny Poppa, Amah dressed him up in Hannah’s old baby clothes.

Hartog: Yes Kate, but it wasn’t very funny for the people coming out of the church on Sunday morning!

Hartog turns to William.

I trust the young soldier has now built an enclosure to ensure Mr Goat keeps out of my daughter-in-laws garden?

Grey: laughs. Now come here Kate and tell me about what you have been reading.

* * * * *

TONI: In this second example, I present an extract from a published factionalised story (Bruce, 2014) that created truths out of “shards of evidence” (Atkinson 1992, p. 46) from a longitudinal study of the meaning of rugby world cups to New Zealanders. For this article, I created a composite female character (the ‘I’ in the excerpt below) who writes a weekly blog during the 2011 Rugby World Cup because she feels it is the only safe space in which to express her ambivalent feelings towards rugby’s dominance in New Zealand culture. The content of the blogs emerged from a four-month period of intensive fieldwork, including attending games, observations in public spaces (fan zones, outside the stadium, bars) and private homes, as well as the results of a small, self-selecting online survey, analysis of media coverage and public comments, and my own lifetime of watching rugby games. Much of what the protagonist writes is word-for-word from the original data, combining the voices of men and women, people of different age groups, occupations and levels of fandom into what is, hopefully, a believable character who helps readers “grapple with multiple contradictions” in her experiences: for example, how she is “enmeshed” in rugby and “highly knowledgeable despite her stated dislike” of the sport or how “her resistance to rugby’s articulation to nationalism is moderated in the face of the pleasures it brings to those with whom she is most intimately and privately involved” (Bruce, 2014, p. 40).

Blog 11 October 19, All Blacks beat Australia 20-6 in Auckland semi-final

This week I let myself get talked into going to a pub near Eden Park for the semi-final. Even though it was a Sunday night, it was total madness. Somehow the hype has become real. Even two hours before the 9pm kick-off, most bars were full and some even had lines outside. It was a sea of black and I even saw an older woman dart across the street in a fashionable little black dress, clearly hand-made from two silver fern flags. We eventually found a spot in a bar about five streets away with a good view of a massive projection screen. Two hours ensued of obsessive discussion about the strengths and weaknesses of every player, including Stephen Donald, unexpectedly called into the team because of injuries. My husband got really worked up. “Bloody Donkey Donald.” Looking my way, he asked “You remember him? He used to play for Waikato.” I nodded. I can’t avoid knowing the Waikato players since my husband is a long-time fan, having grown up on a farm near Hamilton. Satisfied, he wound up again. “How could they pick him? He played like crap last year. Totally lost the plot in the Hong Kong game. Missed his kicks and they lost. That’s why they dropped him. What’s going on in their heads? And he’s totally out of shape. He was whitebaiting when he got the call, for God’s sake. Did you see his belly hanging out?” I nodded like it mattered. When I said, “That doesn’t seem very fair,” that just set him off again. “What? Getting dropped? Of course it is! If you can’t do the job, if you can’t deal with the pressure, then you’re out. He totally lost his confidence. He couldn’t kick for shit. So he had to go.” I can see the others nodding in agreement. I feel sorry for Donald. It’s not like he expected to be playing.

In the end it was a good night out. The Kiwis more than matched the lone Australian who stood to bellow his national anthem, and the Maori and English verses resounded into every corner of the packed bar. 15 It was almost completely silent for the haka. I people-watched, drank wine and surreptitiously checked the online news on my phone. I found a survey, “Will you be concerned if Stephen Donald takes the field in the Rugby World Cup semifinal?” Because I can’t bear the way everyone is picking on him, I vote “No, he’s got the skills.” The vast majority of 11,000 voters went for “Yes, he’s a choker” so I’m yet again in the minority.

Until it became clear the All Blacks couldn’t lose, my husband sat like a bird dog on point; on the edge of his seat, motionless, poised, focused on the action. At the end, while most others stood and cheered and clapped, he collapsed into his chair, leaning back, his eyes closed, a huge smile creasing his face. He and my sister high-fived and toasted each other, but the jubilation didn’t last long. Too much was on the line. “I’m afraid to hope,” he said. “I don’t want to get my hopes up against France. They’ve been dashed too many times before.” All I can think is thank God there’s only one more week to go.

* * * * *

We conclude by restating our belief that factionalisation is a powerful method of inquiry and representation that has much to offer researcher-writers who want to bring research stories to life, to reach readers on emotional and intellectual levels, and to share research beyond the academy. Through the process of creating ‘storied’ versions of our research, we come to ‘know’ our research contexts differently. We also experience the pleasure of ‘playing’ with data, using our imaginations as a tool, and finding creative ways to fill in gaps and reveal silences, hidden truths and sometimes difficult knowledges.

List of references

Atkinson, Paul. 1992. Understanding Ethnographic Texts. Sage, Newbury Park.

Bruce, T. (2014, Dec). Roaming the boundaries of fact and fiction: Making the case for “faction”. Telling Stories Symposium. Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland.

Bruce, T. (2014). A spy in the house of rugby: Living (in) the emotional spaces of nationalism and sport. Emotion, Space and Society, 12, 32-40.

Denshire, S. (2014). On auto-ethnography. Current Sociology Review. 62(6), 831-850.

Fitzpatrick, E. & Bell, A. (2016). Summoning up the Ghost with Needle and Thread. Departures in Critical Qualitative Research. 5.2, Summer 2016; pp. 6-29. DOI: 10.1525/dcqr.2016.5.2.6

Leavy, P. (2016). Fiction as a transformative tool. Commentary. LEARNing landscapes. 9(2).

Markula, P., & Denison, J. (2005). Sport and the personal narrative.” In D.L. Andrews, D.S. Mason & M.L. Silk (Eds.), Qualitative Methods in Sports Studies, (pp. 165-184). Oxford & NY: Berg.

Richardson, L. (2000). New writing practices in qualitative research. Sociology of Sport Journal, 17, 5-20.

Richardson, L. (1994). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 516-529). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Smorti, A. (2011). Autobiographical memory and autobiographical narrative. Narrative Inquiry, 21(2), 303-310. 10.1075/ni.21.2.08smo

Further examples of factionalisation:

Fitzpatrick, E. (2017). A Story of Becoming: Entanglement, Ghosts and Postcolonial Counterstories. Special Issue: Decolonizing Autoethnography. Cultural Studies «—» Critical Methodologies. doi: 10.1177/1532708617728954.

http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1532708617728954?ai=1gvoi&mi=3ricys&af=R

Fitzpatrick, E., & Bell, A. (2016). Summoning up the ghost with needle and thread. Departures in Critical Qualitative Research. 5(2), 1-24.

https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/29396

Heyward, P., & Fitzpatrick, E. (2015). Speaking to the Ghost: An autoethnographic journey with Elwyn. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1-14. doi:10.1080/00131857.2015.1100976

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00131857.2015.1100976?journalCode=rept20